History of the Dickinson Memorial Library

In 1813, Northfield was a prosperous village of shops and farms and multiple small manufacturers. As the nation and the town turned its attention to the War of 1812, a small group of residents met in Houghton’s Tavern and formed the Social Library corporation. Led by Thomas Power, a young lawyer from Boston, the Northfield Social Library was the first in the county to be formed under a 1798 act of the General Court which granted the “proprietors” of such a library the right “to manage the same.”

In 1813, Northfield was a prosperous village of shops and farms and multiple small manufacturers. As the nation and the town turned its attention to the War of 1812, a small group of residents met in Houghton’s Tavern and formed the Social Library corporation. Led by Thomas Power, a young lawyer from Boston, the Northfield Social Library was the first in the county to be formed under a 1798 act of the General Court which granted the “proprietors” of such a library the right “to manage the same.”

The original proprietors of the Northfield Social Library included members of some of the town’s oldest and most prominent families. Meeting for the first time on February 4, 1813, the proprietors each paid $4–then roughly a month’s salary for a day laborer-for the privilege of membership in the Social Library. That money, plus fines for lost or overdue books, went to the purchase of books. By the end of 1813, the library listed seventy works of non-fiction, all housed at Houghton’s Tavern, located conveniently in the center of town. By 1825, the number of titles held by the Social Library had risen to 500, many of them of a religious nature, perhaps a reflection of the tastes of the chair of the purchasing committee, the Reverend Thomas Mason.

Fifty years later, by which time the Social Library had relocated to the former Parson boot factory on the southern end of Main Street, the shareholders voted to relinquish their control of the now almost thousand volume collection. In 1878, the proprietors of the Northfield Social Library leased to the town for a period of 900 years the contents of the library, “on condition that the town spend at least $100 a year for new books.” The town agreed to these terms and the Northfield Public Library was soon opened in Town Hall until such time that a generous benefactor would come forward and provide a suitable building. Twenty years later, such a benefactor made possible the construction of the building now known as the Dickinson Memorial Library. His name was Elijah Marsh Dickinson. Written by Kathleen Banks Nutter

The Legacy of Elijah Dickinson

In the final decades of the 19th century hundreds of public libraries were given to towns by native sons who felt a moral obligation to pass on to others the means for self-improvement. Often given in memory of a relative, these buildings were also cultural centers with art galleries and collections of historical and natural artifacts.

At the age of 80, successful Fitchburg shoe manufacturer Elijah Marsh Dickinson (1816-1902) erected the Dickinson Memorial Library at a cost of $20,000 to honor his Northfield ancestors. Elijah was born in a large brick farmhouse in West Northfield. At 22, like many of his contemporaries, he left the farm to work in industrialized Marlborough, Massachusetts. Within four years, in 1842, he founded his own shoemaking business and the next year married and started a family. In 1854 he moved the enterprise to Fitchburg, where his E.M. Dickinson Shoe Co. became a leading business. 150 workers made 1200 pairs of shoes daily for sale in Boston and the west. Dickinson held various city offices and in 1890 built the Dickinson Block on Main Street, then one of Fitchburg’s finest commercial blocks. Also in 1890 he gave West Northfield the combined Dickinson Hall and school near his boyhood home, which he owned and visited regularly.

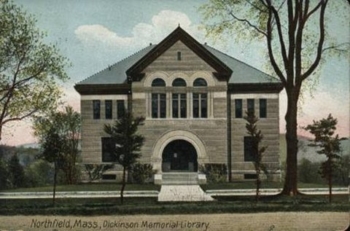

On October 1, 1894 Elijah Dickinson paid library trustee Charles Henry Green $875 for land Green had bought the month before; it was an ideal library site, just yards south of the home built by Elijah’s great-grandfather Nathaniel in 1728, but no longer standing in our day. After the town accepted the building and voted $2000 for furnishings, construction began in 1897 with granite quarried in Northfield’s hills.

The architect was Henry Martyn Francis (1836-1908), who designed many of Fitchburg’s major downtown buildings during the booming late 1800s. While his 15 libraries in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont were all variations of his 1884 Fitchburg library plan, each combined the design elements in a unique way; Dickinson Library, in light-colored native granite and deeply carved limestone instead of the more usual brick and brownstone, is one of the most enduringly handsome. Like many Victorian architects, Francis was influenced by the Romanesque style of Boston giant Henry Hobson Richardson, reflected in Dickinson’s round arches over the deeply recessed doorway and above the column-sided windows, rough-faced stone contrasting with horizontal bands of trim, and horizontal groupings of windows. On Dickinson more than most buildings by Francis, exuberant carved vegetation engulfs figures that represent functions of the library: owls for wisdom, Minerva the goddess of art and culture, the father-god Zeus who guards morality, and at the gable corners wonderful heads of Native Americans representing local history. One of the first acts of the library trustees in 1898 was to advertise in local papers for art, Native American artifacts, and town “relics” to fill the three second-floor museum rooms and large adjoining art gallery, now the children’s room. Dickinson himself donated many paintings and antiques during his frequent trips to the library in years to come.

Victorian architects were more concerned with aesthetics than the needs of librarians or patrons: interior spaces were cozy but impractical and stacks inaccessible. Librarians did battle with architects to bring about a change in philosophy, which started to happen about the turn of the century. Approaching the 21st century, library functions and building needs are still changing. Two nearby New Hampshire libraries designed by H.M. Francis in Rindge (1894) and Jaffrey (1895) have built large additions.

On June 9, 1898 visitors flocked to the library dedication at the Congregational Church by carriage, bicycle, and a large contingent by train from Fitchburg. The keys were received by Dr. Norman P. Wood, who was to continue as chairman of the library trustees for 32 years. After the Seminary girls sang, evangelist D. L. Moody, one of the speakers, asked them to turn toward the elderly donor and sing the Northfield Benediction: “The Lord bless thee and keep thee…” The final speaker, Rev. G. Glenn Atkins of Greenfield, reiterated that townspeople must now keep the library vital by saying, “I reaffirm that your responsibility is great.” He continued,

“This library will be what you make it. You must give it financial support, give generously, regularly, and keep at it… Mr. Dickinson gave the library; see to it that it has a beautiful soul.”

— Written by Betty Congdon

Architectural Detail Photographs

Take a look at these photographs taken by Carlos and Kathy Heiligmann, for their project on public libraries. They show some of the library’s most interesting architectural details.